Contents

Class 19: AI & the Markets

The Financial and Product Markets

- §§ 1 & 8 (pages 1-7 & 24-26) of Sara Fish, Yannai A. Gonczarowski & Ran Shorrer, Algorithmic Collusion by Large Language Models (Nov. 27, 2024), arXiv:2404.00806v2 [econ.GN]

- 1-6 (lines 1-123) & 9-14 (lines & 184-296) of Philipp Winder, Christian Hildebrand & Jochen Hartmann, Biased_Echos: Generative AI Models Reinforce Investment Biases and Increase Portfolio Risks of Private Investors (Nov. 8, 2024).

- Pages 1754-1587 (top 2 lines) & 1590-1592 (top six lines) & 1596-1602 & 1607-1612 (top five lines) of Tejas N. Narechania, Machine Learning as Natural Monopoly, 107 Iowa L. Rev. 1543 (2022).

- Parts 2.2-2.5 (pages 8-14), Parts 4-6 (pages 17-30), and the chart on page 32, of Jon Danielsson & Andreas Uthemann, On the use of artificial intelligence in financial regulations and the impact on financial stability (Feb. 2024).

- Sections 3 & 4 (Pages 9-27) of (UK) Financial Stability Board, The Financial Stability Implications of Artificial Intelligence (Nov. 14, 2024).

- Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President and Competition Commissioner, European Commission Sarah Cardell, Chief Executive Officer, U.K. Competition and Markets Authority Jonathan Kanter, Assistant Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice Lina M. Khan, Chair, U.S. Federal Trade Commission, Joint Statement on Competition in Generative AI Foundation Models and AI Products, Joint Statement on Competition in Generative AI Foundation Models and AI Products (Jul 23, 2024).

The Labor Market

- They Will Displace Us–Or Just Boss Us?

- Rob Thubron, Company cuts costs by replacing 60-strong writing team with AI (June 25, 2024). Note the chart!

- Pages 1-8 Madeline C. Elish, (Dis)Placed Workers: A Study in the Disruptive Potential of Robotics and AI, WeRobot (2018 Working Draft).

- Drew Harwell, Contract lawyers face a growing invasion of surveillance programs that monitor their work, Wash Post (Nov. 11, 2021)

- Wait! Maybe They Are Not Coming to Take (All) Our Jobs?

- Will Knight, Robots Won’t Close the Warehouse Worker Gap Anytime Soon, Wired (Nov. 26, 2021).

- Miho Inada, Humanoid Robot Keeps Getting Fired From His Jobs, Wall St. J. (July 13, 2021).

- Will there be a resistance?

- Robert Wells, Robots, AI Not as Welcomed in Nations Where Income Inequity is High, UCF Today (Aug. 24, 2022).

Optional Readings

General / Regulatory

- CFTC Staff Advisory, Use of Artificial Intelligence in CFTC-Regulated Markets (Dec. 5, 2024).

- Read the rest of Jon Danielsson & Andreas Uthemann, On the use of artificial intelligence in financial regulations and the impact on financial stability (Feb. 2024):

- Artificial intelligence (AI) can undermine financial stability because of malicious use, misaligned AI engines and since financial crises are infrequent and unique, frustrating machine learning. Even if the authorities prefer a conservative approach to AI adoption, it will likely become widely used by stealth, taking over increasingly high-level functions, driven by significant cost efficiencies and its superior performance on specific tasks. We propose six criteria against which to judge the suitability of AI use by the private sector for financial regulation and crisis resolution and identify the primary channels through which AI can destabilise the system.

- Contrast Pages 2-5 & 35-36 of Emilio Calvano, et al., Artificial Intelligence, Algorithmic Pricing and Collusion (Dec. 11, 2019), with Cento Veljanovski, What Do We Now Know About ‘Machine Collusion’, 13 J. European Competition L. & Prac. (2022).

- (*) Daniel Schwarcz, Tom Baker & Kyle D. Logue, Regulating Robo-advisors in an Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence, Washington and Lee Law Review (forthcoming 2025):

- New generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools can increasingly engage in personalized, sustained and natural conversations with users. This technology has the capacity to reshape the financial services industry, making customized expert financial advice broadly available to consumers. However, AI’s ability to convincingly mimic human financial advisors also creates significant risks of large-scale financial misconduct. Which of these possibilities becomes reality will depend largely on the legal and regulatory rules governing “robo-advisors” that supply fully automated financial advice to consumers. This Article consequently critically examines this evolving regulatory landscape, arguing that current U.S. rules fail to adequately limit the risk that robo-advisors powered by generative AI will convince large numbers of consumers to purchase costly and inappropriate financial products and services. Drawing on general principles of consumer financial regulation and the EU’s recently enacted AI Act, the Article proposes addressing this deficiency through a dual regulatory approach: a licensing requirement for robo-advisors that use generative AI to help match consumers with financial products or services, and heightened ex post duties of care and loyalty for all robo-advisors. This framework seeks to appropriately balance the transformative potential of generative AI to deliver accessible financial advice with the risk that this emerging technology may significantly amplify the provision of conflicted or inaccurate advice.

- Brandon Vigliarolo, Investment advisors pay the price for selling what looked a lot like AI fairy tales, The Register (Mar. 18, 2024):

- Two investment advisors have reached settlements with the US Securities and Exchange Commission for allegedly exaggerating their use of AI, which in both cases were purported to be cornerstones of their offerings.

Canada-based Delphia and San Francisco-headquartered Global Predictions will cough up $225,000 an $175,000 respectively for telling clients that their products used AI to improve forecasts. The financial watchdog said both were engaging in “AI washing,” a term used to describe the embellishment of machine-learning capabilities.

- Two investment advisors have reached settlements with the US Securities and Exchange Commission for allegedly exaggerating their use of AI, which in both cases were purported to be cornerstones of their offerings.

- Carla R. Reyes, Autonomous Corporate Personhood, 96 Wash. L. Rev. 1453 (2021):

- “Several states have recently changed their business organization law to accommodate autonomous businesses—businesses operated entirely through computer code. A variety of international civil society groups are also actively developing new frameworks and a model law—for enabling decentralized, autonomous businesses to achieve a corporate or corporate-like status that bestows legal personhood. Meanwhile, various jurisdictions, including the European Union, have considered whether and to what extent artificial intelligence (AI) more broadly should be endowed with personhood to respond to AI’s increasing presence in society. Despite the fairly obvious overlap between the two sets of inquiries, the legal and policy discussions between the two only rarely overlap. As a result of this failure to communicate, both areas of personhood theory fail to account for the important role that socio-technical and socio-legal context plays in law and policy development. This Article fills the gap by investigating the limits of artificial rights at the intersection of corporations and artificial intelligence. Specifically, this Article argues that building a comprehensive legal approach to artificial rights—rights enjoyed by artificial people, whether corporate entity, machine, or otherwise—requires approaching the issue through a systems lens to ensure that the legal system adequately considers the varied socio-technical contexts in which artificial people exist.”

- (*) Seth C. Oranburg, Machines and Contractual Intent (Draft. Jan. 2022):

- “Machines are making contracts—law is not ready. This paper describes why machine-made contracts do not fit easily into the common law of contracts or the Uniform Commercial Code for Sales. It discusses three ways to fit machine-made contracts into common law and discusses the challenges with each approach. Then it presents a new UCC Sales provision that uses Web3 concepts”.

- (*) Daniel Kiat Boon Seng & Cheng Han Tan, Artificial Intelligence and Agents (Oct. 2021):

- “With the increasing sophistication of AI and machine learning as implemented in electronic agents, arguments have been made to ascribe to such agents personality rights so that they may be treated as agents in the law. The recent decision by the Australian Federal Court in Thaler to characterize the artificial neural network system DABUS as an inventor represents a possible shift in judicial thinking that electronic agents are not just automatic but also autonomous. In addition, this legal recognition has been urged on the grounds that it is only by constituting the electronic agents as legal agents that their human principals may be bound by the agent’s actions and activities, and that a proper foundation of legal liability may be mounted against the human principal for the agent’s misfeasance. This paper argues otherwise. It contends that no matter how sophisticated current electronic agents may be, they are still examples of Weak AI, exhibit no true autonomy, and cannot be constituted as legal personalities. In addition, their characterization as legal agents is unnecessary ….”

Finance / Price Theory

- (*) Wojtek Buczynski et al., Future Themes in Regulating Artificial Intelligence in Investment Management, 56 Comp. L & Sec. Rev. 106111 (2025):

- We are witnessing the emergence of the “first generation” of AI and AI-adjacent soft and hard laws such as the EU AI Act or South Korea’s Basic Act on AI. In parallel, existing industry regulations, such as GDPR, MIFID II or SM&CR, are being “retrofitted” and reinterpreted from the perspective of AI. In this paper we identify and analyze ten novel, “second generation” themes which are likely to become regulatory considerations in the near future: non-personal data, managerial accountability, robo-advisory, generative AI, privacy enhancing techniques (PETs), profiling, emergent behaviours, smart contracts, ESG and algorithm management. The themes have been identified on the basis of ongoing developments in AI, existing regulations and industry discussions. Prior to making any new regulatory recommendations we explore whether novel issues can be solved by existing regulations. The contribution of this paper is a comprehensive picture of emerging regulatory considerations for AI in investment management, as well as broader financial services, and the ways they might be addressed by regulations – future or existing ones.

- Dirk A. Zetzsche, Douglas W. Arner, Ross P. Buckley & Brian Tang, Artificial Intelligence in Finance: Putting the Human in the Loop, 43 Syndey L. Rev. 43 (2021):

- “We argue that the most effective regulatory approaches to addressing the role of AI in finance bring humans into the loop through personal responsibility regimes, thus eliminating the black box argument as a defence to responsibility and legal liability for AI operations and decision.”

- Hans-Tho Normann & Martin Sternberg, Hybrid Collusion: Algorithmic Pricing in Human-Computer Laboratory Markets (May 2021):

- “We investigate collusive pricing in laboratory markets when human players interact with an algorithm. We compare the degree of (tacit) collusion when exclusively humans interact to the case of one firm in the market delegating its decisions to an algorithm. We further vary whether participants know about the presence of the algorithm. We find that threefirm markets involving an algorithmic player are significantly more collusive than human-only markets. Firms employing an algorithm earn significantly less profit than their rivals. For four-firm markets, we find no significant differences. (Un)certainty about the actual presence of an algorithm does not significantly affect collusion.”

- Daniel W. Slemmer, Artificial Intelligence & Artificial Prices: Safeguarding Securities Markets from Manipulation by Non-Human Actors, 14 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. (2020):

- “Problematically, the current securities laws prohibiting manipulation of securities prices rest liability for violations on a trader’s intent. In order to prepare for A.I. market participants, both courts and regulators need to accept that human concepts of decision-making will be inadequate in regulating A.I. behavior. Industry regulators should … require A.I. users to harness the power of their machines to provide meaningful feedback in order to both detect potential manipulations and create evidentiary records in the event that allegations of A.I. manipulation arise.”

- Gary Gensler and Lily Bailey, Deep Learning and Financial Stability (Working Paper, Nov. 1, 2020):

- This paper maps deep learning’s key characteristics across five possible transmission pathways exploring how, as it moves to a mature stage of broad adoption, it may lead to financial system fragility and economy-wide risks. Existing financial sector regulatory regimes – built in an earlier era of data analytics technology – are likely to fall short in addressing the systemic risks posed by broad adoption of deep learning in finance. The authors close by considering policy tools that might mitigate these systemic risks.

- Pascale Chapdelaine, Algorithmic Personalized Pricing, 17 NYU Journal of Law & Business,1 (2020):

- “This article provides parameters to delineate when algorithmic personalized pricing should be banned as a form of unfair commercial practice. This ban would address the substantive issues that algorithmic personalized pricing raises. Resorting to mandatory disclosure requirements of algorithmic personalized pricing would address some of the concerns at a procedural level only, and for this reason is not the preferred regulatory approach. As such, our judgment on the (un)acceptability of algorithmic personalized pricing as a commercial practice is a litmus test for how we should regulate the indiscriminate extraction and use of consumer personal data in the future.”

- (*) Anton Korinekand & Joseph E. Stiglitz, Artificial Intelligence, Globalization, and Strategies for Economic Development, Inst. for New Econ. Thinking Working Paper No. 146 (Feb. 4, 2021):

- “Progress in artificial intelligence and related forms of automation technologies threatens to reverse the gains that developing countries and emerging markets have experienced from integrating into the world economy over the past half century, aggravating poverty and inequality. The new technologies have the tendency to be labor-saving, resource-saving, and to give rise to winner-takes-all dynamics that advantage developed countries. We analyze the economic forces behind these developments and describe economic policies that would mitigate the adverse effects on developing and emerging economies while leveraging the potential gains from technological advances. We also describe reforms to our global system of economic governance that would share the benefits of AI more widely with developing countries

- Megan Ji, Are Robots Good Fiduciaries? Regulating Robo-Advisors Under The Investment Advisers Act Of 1940, 117 Columb. L. Rev. 1543 (2017):

- “In the past decade, robo-advisors—online platforms providing investment advice driven by algorithms—have emerged as a low-cost alternative to traditional, human investment advisers. This presents a regulatory wrinkle for the Investment Advisers Act, the primary federal statute governing investment advice. Enacted in 1940, the Advisers Act was devised with human behavior in mind. Regulators now must determine how an automated alternative fits into the Act’s framework.

“A popular narrative, driven by investment advice professionals and the popular press, argues that robo-advisors are inherently structurally incapable of exercising enough care to meet Advisers Act standards. This Note draws upon common law principles and interpretations of the Advisers Act to argue against this narrative. It then finds that regulators should instead focus on robo-advisor duty of loyalty issues because algorithms can be programmed to reflect a firm’s existing conflicts of interest. The Note concludes by arguing for a shift in regulatory focus and proposing a two-part heightened disclosure rule that would make robo-advisor conflicts of interest more transparent.”

- “In the past decade, robo-advisors—online platforms providing investment advice driven by algorithms—have emerged as a low-cost alternative to traditional, human investment advisers. This presents a regulatory wrinkle for the Investment Advisers Act, the primary federal statute governing investment advice. Enacted in 1940, the Advisers Act was devised with human behavior in mind. Regulators now must determine how an automated alternative fits into the Act’s framework.

Taxation

- Robert Kovacev, A Taxing Dilemma: Robot Taxes and the Challenges of Effective Taxation of AI, Automation and Robotics in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, 16 Ohio St. Tech. L.J. 182 (2020):

- Technological change promises major dislocations in the economy, including potentially massive displacement of human workers. At the same time, government revenues dependent on the taxation of human employment will diminish at the very time displaced workers will increasingly demand social services. It is undeniable that drastic changes will have to be made, but until recently there has been little appetite among policymakers for addressing the situation.

One potential solution to this dilemma has emerged in the public discourse over the past few years: the “robot tax.” This proposal is driven by the idea that if robots (and AI and automation) are displacing human workers, and thereby reducing tax revenues from labor-based taxes, then the robots themselves should be taxed […] [Author argues it is a bad idea for many reasons, including we can’t define what is a “robot”. Also argues tax would need to be global to be effective and not providing advantages to those encouraging automation.]

- Technological change promises major dislocations in the economy, including potentially massive displacement of human workers. At the same time, government revenues dependent on the taxation of human employment will diminish at the very time displaced workers will increasingly demand social services. It is undeniable that drastic changes will have to be made, but until recently there has been little appetite among policymakers for addressing the situation.

- Benjamin Alarie, AI and the Future of Tax Avoidance, 181 Tax Notes Fed. 1808 (Dec. 4, 2023):

- I predict that the influence of AI in tax avoidance will be deeply transformative for our tax and legal systems, demarcating a shift to algorithms capable of interpreting the intricacies of tax legislation worldwide, spotting and exploiting trends in legislation and adjudication, and recommending tax minimization strategies to taxpayers and legislative patches to lawmakers. […]

AI can exploit gaps between different tax regimes, necessitating comprehensive responses. These systems, rich in data and analytics, will predict legislative changes and socio-economic impacts, shaping tax law application and planning.

The essay calls for immediate action in rethinking tax policy principles in the AI era. It highlights the importance of dialogue among policymakers, tax practitioners, and technology experts to ensure AI’s integration into tax planning is beneficial, maintains legal integrity, and supports fiscal fairness. The decisions made today regarding AI in tax avoidance will dictate whether the future of tax planning becomes more equitable or further widens the divide between taxpayers and authorities.”

- I predict that the influence of AI in tax avoidance will be deeply transformative for our tax and legal systems, demarcating a shift to algorithms capable of interpreting the intricacies of tax legislation worldwide, spotting and exploiting trends in legislation and adjudication, and recommending tax minimization strategies to taxpayers and legislative patches to lawmakers. […]

AI can exploit gaps between different tax regimes, necessitating comprehensive responses. These systems, rich in data and analytics, will predict legislative changes and socio-economic impacts, shaping tax law application and planning.

- (*) Ryan Abbott & Bret Bogenschneider, Should Robots Pay Taxes? Tax Policy in the Age of Automation, 12 Harv. L. & Pol. Rev. 145 (2018):

- “The tax system incentivizes automation even in cases where it is not otherwise efficient. This is because the vast majority of tax revenues are now derived from labor income, so firms avoid taxes by eliminating employees. Also, when a machine replaces a person, the government loses a substantial amount of tax revenue—potentially hundreds of billions of dol- lars a year in the aggregate. All of this is the unintended result of a system designed to tax labor rather than capital. Such a system no longer works once the labor is capital. Robots are not good taxpayers.

“We argue that existing tax policies must be changed. The system should be at least “neutral” as between robot and human workers, and automation should not be allowed to reduce tax revenue. This could be achieved through some combination of disallowing corporate tax deductions for automated workers, creating an “automation tax” which mirrors existing unemployment schemes, granting offsetting tax preferences for human workers, levying a corporate self-employment tax, and increasing the corporate tax rate.”

- “The tax system incentivizes automation even in cases where it is not otherwise efficient. This is because the vast majority of tax revenues are now derived from labor income, so firms avoid taxes by eliminating employees. Also, when a machine replaces a person, the government loses a substantial amount of tax revenue—potentially hundreds of billions of dol- lars a year in the aggregate. All of this is the unintended result of a system designed to tax labor rather than capital. Such a system no longer works once the labor is capital. Robots are not good taxpayers.

- Robert D. Atkinson, The Case Against Taxing Robots, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (April 8, 2019):

- Robot taxers make three main arguments in support of their position:

1. If we do not tax robots, then government revenues will decline, because few people will be working;

2. If we do not tax robots, then income inequality will grow, because the share of national income going to labor will fall; and

3. Taxing robots would make the economy more efficient, because governments already tax labor, so not taxing robots at the same rate would reduce allocation efficiency.

As this paper will show, all three arguments are wrong. - (FWIW I think that the third issue is a real one.)

- Robot taxers make three main arguments in support of their position:

Competition Law (Anti-trust)

- (*) Satya Marar, Artificial Intelligence and Antitrust Law: A Primer (Mar. 2, 2024):

- Artificial intelligence (AI) embodies rapidly evolving technologies with great potential for improving human life and economic outcomes. However, these technologies pose a challenge for antitrust enforcers and policymakers. Shrewd antitrust policies and enforcement based on a cost-benefit analysis support a thriving pro-innovation economy that facilitates AI development while mitigating its potential harms. Misguided policies or enforcement can stymie innovation, undermine vigorous economic competition, and deter research investment. This primer is a guide for policymakers and legal scholars that begins by explaining key concepts in AI technology, including foundation models, semiconductor chips, cloud computing, data strategies and others. The next section provides an overview of US antitrust laws, the agencies that enforce them, and their powers. Following that is a brief history of US antitrust law and enforcement with a focus on the consumer welfare standard, its basis and benefits, and the flaws underlying recent calls by the Neo-Brandeisian movement to abandon it. Finally, the primer outlines the law and a procompetitive, pro-innovation policy framework for approaching the intersection between AI technologies and evaluating horizontal and vertical mergers, policing anticompetitive monopolization practices, price fixing and algorithmic collusion, and consumer protection issues.

- (*) Robin Feldman & Caroline A. Yuen, AI and Antitrust: “The Algorithm Made Me Do It” (Oct. 24, 2024):

- As the dawn of AI rises rapidly, competition authorities may wish to contemplate the potential for hazy days ahead. Undoubtedly, AI offers exciting possibilities for society-from sparking innovation, to enhancing efficiency, to easing life’s burdens, to leveling the playing field for non-native speakers. Nevertheless, the future of AI may bring more than the opportunity to bask in its glow. As AI becomes a more accurate and skillful tool, it could conceivably lead to more anticompetitive hub-and-spokes arrangements that current competition laws may not be fully equipped to evaluate. Using the pharmaceutical supply chain as an example of an industry with concentrated intermediaries, this article discusses how such structures are tacit collusion, and how AI is likely to exacerbate the issue.

- Samuel Weinstein, Pricing Algorithms—What Role For Regulation?, Competition Policy International Antitrust Chronicle (Feb. 2024):

- The rapid spread of pricing algorithms in e-commerce markets has raised alarms about their potential for anticompetitive abuse. Enforcers and policy-makers have been concerned for some time about the possibility of widespread algorithmic price-fixing and dominant firms’ use of algorithms to damage rivals. These harms are in theory redressable under the antitrust laws. But evidence is mounting that pricing algorithms will raise prices to consumers in ways that do not violate the antitrust laws. Tacit algorithmic collusion and price increases due to competition among pricing algorithms will make many online goods and services more expensive. Consumers currently have no effective way to fight back against these higher prices. Market-based solutions, like consumer-friendly algorithms that steer buyers to the best prices, can help. But considering the scope and scale of the ongoing revolution in pricing technology, protecting consumers is likely to require a regulatory response. Regulations that limit when and how firms set prices could restrict algorithms’ ability to raise prices above the competitive level. While not costless, this approach might be necessary to prevent a significant transfer of wealth from consumers to sellers.

- Cary Coglianese & Alicia Lai, Algorithms and Competition in the Digital Economy, e-Competitions, Special issue Algorithms & Competition, (Oct. 4, 2023):

- The global economy is increasingly a digital economy driven by algorithms. This shift to a digital or algorithmic economy poses some distinct implications for how antitrust and consumer protection law evolves in the future. With this Foreword to a special issue published by Concurrences , we highlight major antitrust-related legal developments occurring around the world in response to the rapidly emerging environment of algorithmic-driven commerce. Without necessarily endorsing nor rejecting any of the various policies or proposals that have occurred in recent years, we organize and describe key antitrust-related legal developments that have arisen in response to the growth of the digital economy. In Part I, we detail some of the major legal changes or proposed changes that have targeted digital technology firms. Although many of these targeted firms deploy services that use algorithmic tools, competition authorities have not yet begun to do as much to regulate algorithmic services themselves as to target the firms that make use of them. And even though the specifics of some of the regulatory actions targeting digital firms can be said to be distinctive in their focus on online and other digital businesses, many of the concerns underlying regulatory actions or proposals have been, to date, similar to those that have long applied to general business activity. In Part II, we highlight an aspect of antitrust that might become truly novel in an increasingly algorithmic economy: the targeting of antitrust law and principles to business actions driven by algorithms themselves. As algorithmic tools come to automate economic transactions and autonomously make business decisions, the object of governmental oversight may well shift from the traditional focus on human managers to machine ones—or perhaps to the human designers of machine-learning “managers.” This is an emerging possibility which to date can be most saliently seen in the context of self-preferencing algorithms. Although antitrust enforcers appear thus far to target types of self-preferencing behaviors that have emanated from human decisions rather than fully independent algorithmic ones, it is not hard to conceive a future in which AI autonomously drives business decisions in problematic, anticompetitive directions or that operate on their own to charge supracompetitive prices. Finally, in Part III, in the face of a future that seems likely to be dominated by algorithmic transformations throughout the economy, antitrust regulators can expect to face a growing need themselves to develop and rely upon artificial intelligence and other algorithmic tools. The transition to an algorithmic economy, in the end, not only raises new sources of concern about competition and consumer protection, but it may also provide government with new opportunities to use digital tools to advance the goals of fair and efficient economic competition.

Labor Markets

- (*) Mauro Cazzaniga et al., International Monetary Fund, Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (Jan. 2024):

- Artificial intelligence (AI) is set to profoundly change the global economy, with some commentators seeing it as akin to a new industrial revolution. Its consequences for economies and societies remain hard to foresee. This is especially evident in the context of labor markets, where AI promises to increase productivity while threatening to replace humans in some jobs and to complement them in others.Almost 40 percent of global employment is exposed to AI, with advanced economies at greater risk but also better poised to exploit AI benefits than emerging market and developing economies. In advanced economies, about 60 percent of jobs are exposed to AI, due to prevalence of cognitive-task-oriented jobs. …AI will affect income and wealth inequality. Unlike previous waves of automation, which had the strongest effect on middle-skilled workers, AI displacement risks extend to higher-wage earners.[…] Owing to capital deepening and a productivity surge, AI adoption is expected to boost total income. [….]Younger workers who are adaptable and familiar with new technologies may also be better able to leverage the new opportunities.[…] To harness AI’s potential fully, priorities depend on countries’ development levels. A novel AI preparedness index shows that advanced and more developed emerging market economies should invest in AI innovation and integration, while advancing adequate regulatory frameworks to optimize benefits from increased AI use. For less prepared emerging market and developing economies, foundational infrastructural development and building a digitally skilled labor force are paramount. For all economies, social safety nets and retraining for AI-susceptible workers are crucial to ensure inclusivity.

- (*) United Nations, Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Technology & International Labor Organization, Mind the AI Divide: Shaping a Global Perspective (2024):

- There is a pronounced “AI divide” emerging, where high income nations disproportionately benefit from AI advancements, while low- and medium-income countries, particularly in Africa, lag behind. Worse, this divide will grow unless concerted action is taken to foster international cooperation in support of developing countries. The absence of such policies will not only widen global inequalities, but risks squandering the potential of AI to serve as a catalyst for widespread social and economic progress. While AI will potentially affect many aspects of our daily lives, its impact is likely to be most acute in the workplace. Wealthier countries are more exposed to the potential automating effects of AI in the world of work, but they are also better positioned to realize the productivity gains it offers. Developing countries, on the other hand, may be temporarily buffered because of a lack of digital infrastructure, but this buffer risks turning into a bottleneck for productivity growth, and more importantly,

- (*) DATA

- Kunal Handa et al., Anthropic, Which Economic Tasks are Performed with AI? Evidence from Millions of Claude Conversations (Feb 16, 2025):

- Despite widespread speculation about artificial intelligence’s impact on the future of work, we lack systematic empirical evidence about how these systems are actually being used for different tasks. Here, we present a novel framework for measuring AI usage patterns across the economy. We leverage a recent privacy-preserving system [Tamkin et al., 2024] to analyze over four million Claude.ai conversations through the lens of tasks and occupations in the U.S. Department of Labor’s O*NET Database. Our analysis reveals that AI usage primarily concentrates in software development and writing tasks, which together account for nearly half of all total usage. However, usage of AI extends more broadly across the economy, with ~ 36% of occupations using AI for at least a quarter of their associated tasks. We also analyze how AI is being used for tasks, finding 57% of usage suggests augmentation of human capabilities (e.g., learning or iterating on an output) while 43% suggests automation (e.g., fulfilling a request with minimal human involvement). While our data and methods face important limitations and only paint a picture of AI usage on a single platform, they provide an automated, granular approach for tracking AI’s evolving role in the economy and identifying leading indicators of future impact as these technologies continue to advance.

- Xiao Ni, et al, Generative AI in Action: Field Experimental Evidence on Worker Performance in E-Commerce Customer Service Operations (Nov 9, 2024):

- In collaboration with Alibaba, this study leverages a large-scale field experiment to quantify the impact of a generative AI (gen AI) assistant on worker performance in an e-commerce after-sales service setting, where human agents provide customer support through digital chat. Agents were randomly assigned to either a control or treatment group, with the latter having access to a gen AI assistant that offers two automated functions as text messages: 1) diagnosis of customer order issues in real time and 2) solution suggestions. Agents exhibited varied gen AI usage behavior, choosing to use, modify, or disregard AI suggested messages. We employ two empirical approaches: 1) an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis to estimate the average treatment effect of gen AI access, and 2) a local average treatment effect (LATE) analysis to estimate the causal impact of gen AI usage. Results show that the gen AI assistant significantly enhanced both service speed and service quality. Interestingly, gen AI automation did not lead agents to reduce effort; rather, it increased their engagement, evidenced by a higher message volume and agent-to-customer message ratio. Analysis by agents’ pretreatment performance reveals that low performers experienced greater improvements in speed and quality, narrowing the performance gap, while high performers saw a decline in service quality, likely because gen AI suggestions fell below their expertise. These findings underscore the potential of gen AI to improve operational efficiency and service quality while highlighting the need for tailored deployment strategies to support workers with varying skill levels.

- James Wright, Inside Japan’s long experiment in automating elder care, MIT Tech Rev. (Jan 9, 2023)

- “A growing body of evidence is finding that robots tend to end up creating more work for caregivers.”

- Francesco Filippucci, Peter Gai & Matthias Schief, CEPR, Miracle or myth: Assessing the macroeconomic productivity gains from artificial intelligence (Dec. 8, 2024):

- Artificial intelligence has been shown to deliver large performance gains in selected economic activities, but its aggregate impact remains debated. This column discusses a micro-to-macro framework to assess the aggregate productivity gains from AI under different scenarios. AI could contribute between 0.25 and 0.6 percentage points to annual total factor productivity growth in the US over the next decade. However, highly uneven sectoral productivity gains could reduce aggregate growth, and large aggregate gains will require a productive integration of AI in a wide range of economic activities.

- Kunal Handa et al., Anthropic, Which Economic Tasks are Performed with AI? Evidence from Millions of Claude Conversations (Feb 16, 2025):

- Josh Dzieza, How Hard Will the Robots Make Us Work?, The Verge (Feb. 27, 2020).

- Christine Walley, Robots as Symbols and Anxiety over Work Loss (2020).

- (*) Pegah Moradi & Karen Levy, The Future of Work in the Age of AI: Displacement or Risk-Shifting? in Oxford Handbook of Ethics of AI 271 (Markus Dubber, Frank Pasquale, and Sunit Das, eds, 2020):

- This chapter examines the effects of artificial intelligence (AI) on work and workers. As AI-driven technologies are increasingly integrated into workplaces and labor processes, many have expressed worry about the widespread displacement of human workers. The chapter presents a more nuanced view of the common rhetoric that robots will take over people’s jobs. We contend that economic forecasts of massive AI-induced job loss are of limited practical utility, as they tend to focus solely on technical aspects of task execution, while neglecting broader contextual inquiry about the social components of work, organizational structures, and cross-industry effects. The chapter then considers how AI might impact workers through modes other than displacement. We highlight four mechanisms through which firms are beginning to use AI-driven tools to reallocate risks from themselves to workers: algorithmic scheduling, task redefinition, loss and fraud prediction, and incentivization of productivity. We then explore potential policy responses to both displacement and risk-shifting concerns.\

- Xian Hui, Oren Reshef & Luofeng Zhou, The Short-Term Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Employment: Evidence from an Online Labor Market, CESinfo Working paper (August. 2023):

- Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) holds the potential to either complement knowledge workers by increasing their productivity or substitute them entirely. We examine the short-term effects of the recent release of the large language model (LLM), ChatGPT, on the employment outcomes of freelancers on a large online platform. We find that freelancers in highly affected occupations suffer from the introduction of generative AI, experiencing reductions in both employment and earnings. We find similar effects studying the release of other image-based, generative AI models. Exploring the heterogeneity by freelancers’ employment history, we do not find evidence that high-quality service, measured by their past performance and employment, moderates the adverse effects on employment. In fact, we find suggestive evidence that top freelancers are disproportionately affected by AI. These results suggest that in the short term generative AI reduces overall demand for knowledge workers of all types, and may have the potential to narrow gaps among workers.

- Jay Stanley, ACLU, Amazon Drivers Placed Under Robot Surveillance Microscope (March 23, 2021):

- “AI monitoring will soon move beyond [factory workers], starting with less powerful people across our society — who, like Amazon’s nonmanagerial workforce, are disproportionately people of color and are likely to continue to bear the brunt of that surveillance. And ultimately, in one form or another, such monitoring is likely to affect everyone — and in the process, further tilt power toward those who already have it.”

- Leslie Beslie,My Time on the Assembly Line Working Alongside the Robots That Would Replace Us, The Billfold (May 6, 2014).

- Karen Hao, A new generation of AI-powered robots is taking over warehouses, MIT Tech Rev. (Aug 6, 2021).

- Maybe the problem will be … not enough robots? So argues Wilson da Silva, My Robot Friend_ The Promise of Social Robots, Medium (Apr 5, 2020).

- (*) Tough mathy paper: Daron Acemoglu, Claire LeLarge, Pascual Restrepo, Competing with Robots: Firm-Level Evidence from France (NBER Working Paper No. 26738), February 2020, suggests that workers most hurt by robots are firms that compete with the ones using the robots.

- MIT Work of the Future Task Force, The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines (2020).

- News reports (anecdotes?) about robots (many run by an AI) taking jobs:

- Factories (of course), Steven Borowiec, Fearing lawsuits, factories rush to replace humans with robots in South Korea, restofworld.org (June 6, 2022) .

- Hotels: JD Shadel, Robots are disinfecting hotels during the pandemic. It’s the tip of a hospitality revolution, Wash. Post (Jan 27. 2021).

- Restaurants:

- Janet Morissey, Desperate for Workers, Restaurants Turn to Robots, N.Y. Times (Oct. 19, 2021).

- Lauren Saria, This Restaurant Is Run Entirely By Robots, SF Eater (Aug. 17, 2022). (Does this sound attractive?)

- Stores: Mike Oitzman,Restocking robots deployed in 300 Japanese convenience stores, The Robot Report (Aug. 12, 2022) (Note: “Next, Telexistence wants to target the 150,000 convenience stores in the US.”)

Optional related PR video:

- Farms: Farmer George, Tiny Weed-Killing Robots Could Make Pesticides Obsolete, OneZero (July 1, 2020). Alt link

- Hospitals: Andrew Gegory, Robot successfully performs keyhole surgery on pigs without human help, The Guardian (Jan 26, 2022).

Insurance

- (*) International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS), DRAFT Application Paper on the supervision of artificial intelligence (Nov. 2024):

- The adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) systems is accelerating globally. For insurers, these developments offer substantial commercial benefits across the insurance value chain, for example by enhancing policyholder retention through personalised engagement, achieving significant cost reductions via increased efficiency in policy administration and claims management, or applying AI capabilities to improve risk selection and pricing.2. However, with these advancements come notable risks that could detrimentally impact the financial soundness of insurers […] and consumers as well). For example, left unchecked, AI systems can reinforce historic societal biases or discrimination and, for individuals, can increase concerns around data privacy. For insurers, the opaque and complex nature of some AI systems can lead to accountability issues, where it becomes difficult to trace decisions or actions back to human operators, and uncertainty of outcomes (particularly in a changing external environment). Addressing such concerns is paramount to maintaining trust and fairness in the industry.[…] 4. This Application Paper reinforces the importance of the [Insurance Core Principles ICPs,} outlining how existing expectations around governance and conduct remain essential considerations for supervisors and insurers using AI. Furthermore, noting that AI can amplify existing risks, this paper emphasises the importance of continued Board and senior manager education in order to establish robust risk and governance frameworks to ensure good consumer outcomes. Additionally, this paper notes that increasing application of AI can heighten the role of third parties like AI model vendors. Consistent with existing ICPs, this paper reaffirms that insurers remain responsible for understanding and managing these systems and their outcomes

- (*) Anat Lior, Insuring AI: The Role of Insurance in Artificial Intelligence Regulation, 35 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 467 (2022):

- “Insurance has the power to better handle AI-inflicted damages, serving both a preventive and compensatory function. This Article offers a framework for stakeholders and scholars working on AI regulation to take advantage of the current robust insurance system. It will discuss the type of insurance policy that should be purchased and the identity of the policyholder. The utilization of insurance as a regulatory mechanism will alleviate the risks associated with the emerging technology of AI while providing increased security to AI companies and AI users. This will allow different stakeholders to continue to unlock the power of AI and its value to society.”

- Brad Templeton, What Happens To Car Insurance Rates After Self-Driving Cars?, Forbes (Sep 21, 2020).

Other Economic Applications

- (*) Elizabeth Blankespoor, Ed deHaan & Qianqian Li, Generative AI in Financial Reporting (Oct 14, 2024):

- Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) such as ChatGPT will likely alter many aspects of the financial reporting process and spawn a deep stream of academic research. We take an early step by examining the extent to which firms have begun using GAI in one important part of the reporting process: writing disclosures. The pre-registration phase of our study evaluates a commercial tool’s ability to detect GAI-modified language in firms’ 10Ks, earnings press releases, and conference call prepared remarks. We find that the tool, GPTZero, is impressively powerful; for example, it reliably identifies GAI in realistic samples when we use GAI to modify as few as 2.5% of sentences in 2.5% of firms’ reports; i.e., when just 0.0625% of text is modified. The postregistration phase examines firms’ actual use of GAI in reports through 2024 and whether GAI usage measurably affects linguistic properties such as disclosure readability — an important factor affecting investor information processing and market outcomes. Our study provides early insights into the use of GAI in financial reporting and motivates future research in this evolving area.

- Modupe James, Auditing AI-Generated Financial Statements (Dec. 20, 2023):

- Unlocking the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized numerous industries, and the world of finance is no exception. As businesses strive to streamline their processes and gain a competitive edge, AI-generated financial statements have emerged as a game-changer. These automated systems can swiftly generate accurate reports, saving auditors valuable time and effort. However, with this incredible innovation comes unique challenges for auditors who must ensure accuracy and compliance in an ever-evolving landscape. In this article, we will explore these challenges and provide essential guidelines for auditors auditing AI-generated financial statements. We will now delve into the fascinating world where cutting-edge technology meets meticulous scrutiny!

AI-generated financial statements are a product of the increasing integration of artificial intelligence in various industries, including finance. These statements are created using algorithms and machine learning techniques to analyze vast amounts of data and generate accurate financial reports.

- Unlocking the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized numerous industries, and the world of finance is no exception. As businesses strive to streamline their processes and gain a competitive edge, AI-generated financial statements have emerged as a game-changer. These automated systems can swiftly generate accurate reports, saving auditors valuable time and effort. However, with this incredible innovation comes unique challenges for auditors who must ensure accuracy and compliance in an ever-evolving landscape. In this article, we will explore these challenges and provide essential guidelines for auditors auditing AI-generated financial statements. We will now delve into the fascinating world where cutting-edge technology meets meticulous scrutiny!

- (*) Przemysław Pałka & Agnieszka Jabłonowska, Consumer Law and Artificial Intelligence in Research Handbook on Law and Artificial Intelligence (Woodrow Barfield & Ugo Pagallo (eds.) (2024):

- The chapter examines developments in artificial intelligence from the point of view of consumer law. First, it offers an overview of various problems consumers might face as a result of a business’s use of AI and explores the ability of existing regulations to combat such threats. Second, it looks at situations where AI is sold as (an element of) a consumer product and points to the relevant legislation. Third, the potential of AI to empower consumers and their organisations is discussed. The goal of the chapter is to provide a broad overview of research directions and literature. It hopes to enable consumer law scholars with a developing interest in AI, as well as AI policy scholars venturing into consumer law, to engage with the most pressing problems at the frontier of research in this area.

- Interesting to compare to articles above and below (and to Weinstein on Pricing Algorithms) …. Michal Gal & Amit Zac, Is Generative AI the Algorithmic Consumer We are Waiting for?, Network L. Rev. (March 2024):

- Most studies on the competitive effects of Generative AI focus on the supply side. Interest in consumers is generally restricted to their roles as users of the technology, as well as indirect trainers of Generative AI models through their prompt engineering. In this short article, we focus instead on the potential effects of Generative AI on competition that arise from an active use of Generative AI on the demand side, by consumers seeking goods and services. In particular, we explore the possibility that Generative AI Large Language Models (LLMs) can act as truncated algorithmic consumers, assisting consumers in deciding which products and services to purchase, thereby potentially reducing consumers’ information costs and increasing competition. We explore how LLMs’ unique characteristics – mainly their conversational use and the provision of an authoritative single answer, as well as spillover trust effects from their other uses – might motivate consumers to use them to search for products and services. We then analyze some of the limitations and competition concerns that might result from the use of Generative AI by consumers. In particular, we show how LLMs’ modus operandi – trained to seek the most plausible next word – lead to outcome homogenization and increase entry barriers for new competitors in product markets. We also explore the potential of manipulation and gaming of LLM models. As elaborated, a combination of an LLM model with a dataset on consumers’ digital profiles might potentially create a strong nudging mechanism, recreating consumer choice architecture to optimize commercial goals and exploiting consumer’s behavioral biases in novel ways not envisioned.

- Horst Eidenmülle, The Advent of the AI Negotiator: Negotiation Dynamics in the Age of Smart Algorithms, 20 J. Bus. Tech. L. (2025):

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications are increasingly used in negotiations. In this essay, I investigate the impact of such applications on negotiation dynamics. A key variable in negotiations is information. Smart algorithms will drastically reduce information and transaction costs, improve the efficiency of negotiation processes, and identify optimal value creation options. The expected net welfare benefit for negotiators and societies at large is huge. At the same time, asymmetric information will assist the algorithmic negotiator, allowing them to claim the biggest share of the pie. The greatest beneficiary of this information power play could be BigTech and big businesses more generally. These negotiators will increasingly deploy specialized negotiation algorithms at scale, exploiting information asymmetries and executing value claiming tactics with precision. In contrast, smaller businesses and consumers will likely have to settle for generic tools like the free version of ChatGPT. However, who will ultimately be the big winners in AI-powered negotiations depends crucially on the laws that regulate the market for AI applications.

- Barak Orbach & Eli Orbach,

- The US Is Not Prepared for the AI Electricity Demand Shock (Oct 24, 2024):

- The United States power grid is increasingly strained by the surging electricity demand driven by the AI boom. Efforts to modernize the power infrastructure are unlikely to keep pace with the rising demand in the coming years. We explore why competition in AI markets may create an electricity demand shock, examine the associated social costs, and offer several policy recommendations.

Notes & Questions

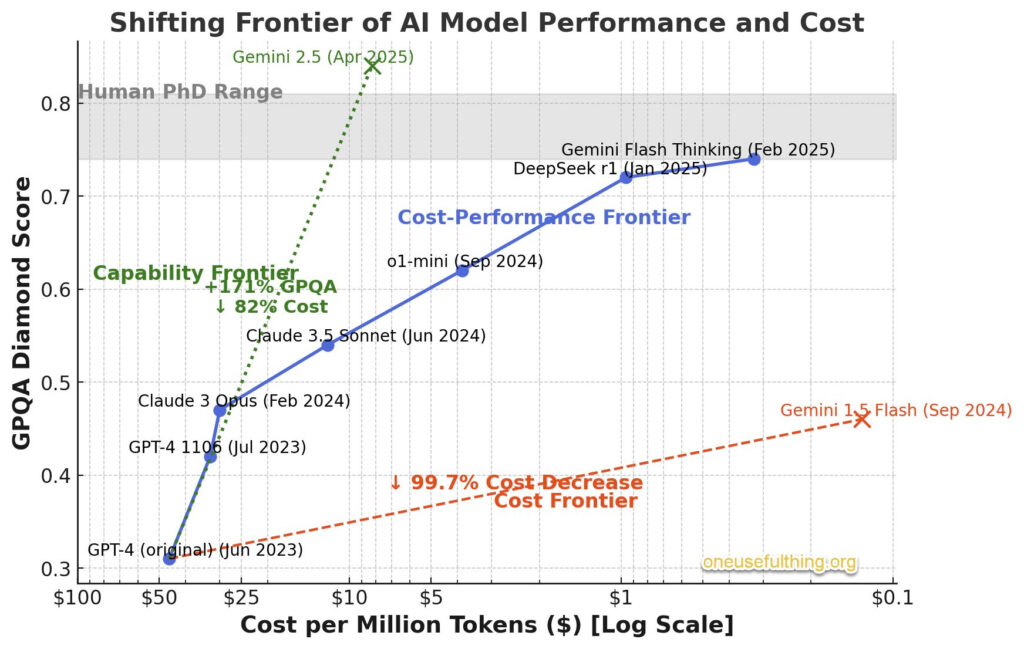

- Narechania argued that ML tends to natural monopoly–due to high barriers to entry, both in hardware and human capital, and due to ‘feedback’ from users that resembles network effects. He offered GPT-3 as an example, albeit two years ago (p. 1583), although that’s a generative model.

- Is the argument equally good for standard ML and for generative AI?

- Has more recent history suggested that maybe one or both don’t fit the natural monopoly story?

- Is there any reason to believe that recent history is atypical, and the ML / GenAI supplier market(s) will soon ‘settle down’ something monopolistic or oligopolistic? Any reason to doubt that?

- Assuming that ML and/or GenAI are natural monopolies in general, or in specific industries, is ordinary anti-trust law sufficient to deal with the problem? If not, what new rules do we need?

- This recent video got a lot of attention

- But in fact there is a back story. Key points: the video was a demo of a special ability programmed into the two chatbots programmed to respond in this fashion if they detected they were conversing with another chatbot. Plus, the AIs didn’t invent the language on their own.

- There is, however, some evidence that chatbots built to cooperate or negotiate might develop at least a shorthand in the wild. The video resonates when one considers the risks of AI cooperation in ways that violate or circumvent legal rules.

- This recent video got a lot of attention

- Is AI really a threat to securities and other markets as we know them?

- If so, what is the solution?

- To the extent you envision an institutional regulatory solution would it be better to

- Put the regulatory authority in an agency whose focus was AI (and might have more technical experts on AI)?

- Put the regulatory authority in one or more existing (or new?) agencies dedicated to regulation of financial markets (e.g. SEC, CFTC, Treasury and/or CFPB)?

- Put the regulatory authority in the FTC which (with the Justice Department) regulates monopolies?

- What substantive rules would we need to head off the risks of

- fraud

- market manipulation (e.g. pump and dump)

- collusion

… to securities and other markets?

- Recall Lynn Lopucki’s argument (Class 8) that by using various corporate devices, an AI could own itself and thus become a legal person to the extent, at least, that we allow corporations to be considered legal persons. Does this alter your view of the economic or regulatory issues discussed in this section?

- Historically, new tech kills some old jobs, but creates as least as many new ones.

- What if anything should we do as a society, or as policy-makers, owe to the losers? Especially if job loss is not their “fault” as the industry changes.

- If the ‘something’ we do involves payments to workers or retraining facilities is this

- a general social responsibility

- or something that should fall particularly on the beneficiaries (makers, sellers, users) of the new technology?

- If this involves training,

- what do we do if the losers (e.g truckers) are not easily trained to do the new tasks (e.g. coding) whether due to educational background, temperament, or age?

- Or is, as Walley suggests, the identification between education level and “skills” largely a myth.

- Or is Andrew Yang today’s visionary and the rise of the robots will force us into a Universal Basic Income?

- Most tech revolutions come with lots of people saying “this time is different”.

- What reasons, if any, do we have for the claim that “this time is different” and thus there could be a net loss of jobs due to robots?

- Note that there are a lot of truckers (estimates range from 1 million to 3.5 million combining long-haul, short haul, and tractor-trailers) and also a lot of retail service jobs (c. 10 million if we include first-level floor supervisors) that might be at risk.

- This revolution might also hit professions:

- Insurance agents,

- Doctors,

- And, yes, lawyers.

- Do we think professionals as a class might be more ‘retrainable’ or movable to new jobs given they usually have more education than truckers, warehoused employees, or assembly line workers? Of course it could mean a pay cut, but that is better than unemployment…

- What reasons, if any, do we have for the claim that “this time is different” and thus there could be a net loss of jobs due to robots?

- What does co-working with robots (sometimes, not so often, called-cobots — co-robotics is a more common term) do to the nature/quality of work? Does it “turn people into robots”? [See optional reading – Leslie Beslie, My Time on the Assembly Line Working Alongside the Robots That Would Replace Us, The Billfold (May 6, 2014)]

- Call center employees are increasingly being replaced by robotic menus. If you do get a human, that person is asked to ‘stick to a script’ and often is dis-empowered from being able to escalate problems or fix any unusual ones. This discourages complaining customers and saves money (firms tend to see call center operations as a cost center, especially after sale, not a branding opportunity).

- Do we say, “that’s capitalism” and move on, or say/do something else?

- If “something else” is our primary concern the worker, or something else?

- Originally the hope was that robots might do the most demanding and dangerous jobs, and that has proved somewhat true if we define “demanding” as “finding and lifting heavy stuff” or “disinfecting hospitals and hotel rooms for COVID”. It’s less true, at least at Amazon, when it comes to more complex sorting tasks. Is this something to worry about, or will it fix itself as robots get better/smarter/more dexterous?

- Modern scheduling algorithms often can predict demand for labor very precisely – but not very far in advance (yet). A consequence is that firms demand workers be available for long periods of the week, but at the last minute may or may not ask them to come into work; no work, no pay. But workers can’t take a second job that might fill those missing hours, because they can’t ever promise to be available in the blocks of time they’ve promised to the first employer. These so-called “zero hours” contracts are the subject of intense debate in the UK and Europe and are partly blamed for the “Great Resignation” in the US. Should they be allowed?

- Call center employees are increasingly being replaced by robotic menus. If you do get a human, that person is asked to ‘stick to a script’ and often is dis-empowered from being able to escalate problems or fix any unusual ones. This discourages complaining customers and saves money (firms tend to see call center operations as a cost center, especially after sale, not a branding opportunity).

- Just because surveys show that people living in Nordic countries are happier and live longer than most other places, is that any reason to look to them as a model for how to structure the employment and public benefits relationships?

- Or can we avoid that horrible fate with a AI/robot tax? (See the Kovacev article in the optional reading if this question interests you.)

- Even if we could in theory go Nordic, if job losses due to automation are as massive as the scariest (if perhaps over-alarmist) estimates suggest, how otherwise will we pay for it? Does the AI/robot tax then become not a way of avoiding ‘going Nordic’ but still paying for it?

- Regardless of the overall political goals, if our tax goal is an efficient “Pigouvian tax” i.e. one equal to the externalities caused by the AI/robot, what do we do if the AI/robot is actually good for society, and has a positive externality? (Do we subsidize it?)

- If we have one, does a AI/robot tax have to be global to be effective? Would national suffice? Would a state-level tax suffice in many states?

Class 20: Ethics Issues

- Brian Patrick Green, Artificial Intelligence and Ethics, Markkula Center for Applied Ethics (Nov. 21, 2017).

- Annette Zimmermann and Bendert Zevenbergen, AI Ethics: Seven Traps, Freedom to Tinker Blog (Mar. 25, 2019).

- Religious Approaches

- Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, Artificial Intelligence: An Evangelical Statement of Principles (April 11, 2019).

- Christian Today, Bishop issues ’10 commandments of Artificial Intelligence’ (Feb. 28, 2018).

- Rome Call for AI Ethics (Feb 28, 2022).

- Professional Approaches

- ACM, Statement on Principles for Responsible Algorithmic Systems (Oct. 26, 2022).

- International Approaches

- United Nations General Assembly, Seizing the opportunities of safe, secure and trustworthy artificial intelligence systems for sustainable development (Adopted on March 21, 2024).

- Lawyers’ Professional Ethics Duties (Review from class 18)

- Florida Bar Ethics Opinion 24-1 (Jan. 19, 2024).

- American Bar Association, Formal Opinion 512 (July 29, 2024)

- Court of International Trade, Order on Artificial Intelligence (June 8, 2023).

- Critique

- Abeba Birhane & Jelle van Dijk,Robot Rights? Let’s Talk about Human Welfare Instead (Jan 14, 2020).

- Daniel Schiff et al, AI Ethics in the Public, Private, and NGO Sectors: A Review of a Global Document Collection, 2 IEEE Trans. Tech. & Soc. 31 (2021).

Optional

In General

- (*) Shumiao Ouyang, Hayong Yun & Xingjian Zheng, How Ethical Should AI Be? How AI Alignment Shapes the Risk Preferences of LLMs (Feb 1, 2025):

- This study examines the risk preferences of Large Language Models (LLMs) and how aligning them with human ethical standards affects their economic decision-making. Testing 50 LLMs across self-reported and simulated investment tasks, we find wide variation in risk attitudes. Notably, models scoring higher on safety metrics tend to exhibit greater risk aversion. Through a direct alignment exercise, we establish that embedding human values—harmlessness, helpfulness, and honesty—causally shifts LLMs toward more cautious decision-making. While moderate alignment improved financial forecasting, excessive alignment led to overcautious decisions that hurt predictive accuracy. This trade-off underscores the need for AI governance that balances ethical safeguards with domain-specific risk-taking, ensuring alignment mechanisms don’t overly hinder AI-driven decision-making in finance and other economic domains.

- (*) Morten Bay, AI Ethics and Policymaking: Rawlsian Approaches to Democratic Participation, Transparency, Accountability, and Prediction (May 31, 2023):

- “The AI ethics field is seeing an increase in explorations of theoretical ethics in addition to applied ethics, and this has spawned a renewed interest in John Rawls’ theory of justice as fairness and how it may apply to AI. But how may these new, Rawlsian contributions inform regulatory policies for AI? This article takes a Rawlsian approach to four key policy criteria in AI regulation: Democratic participation, transparency, accountability, and the epistemological value of prediction. Rawlsian, democratic participation in the light of AI is explored through a critique of Ashrafian’s proposed approach to Rawlsian AI ethics, which is found to contradict other aspects of Rawls’ theories. A turn toward Gabriel’s foundational theoretical work on Rawlsian justice in AI follows, extending his explication of Rawls’ Publicity criterion to an exploration of how the latter can be applied to real-world AI regulation and policy. Finally, a discussion of a key AI feature, prediction, demonstrates how AI-driven, long-term, large-scale predictions of human behavior violate Rawls’ justice as fairness principles. It is argued that applications of this kind are expressions of the type of utilitarianism Rawls vehemently opposes, and therefore cannot be allowed in Rawls-inspired policymaking.”

- Salla Westerstrand, Reconstructing AI Ethics Principles: Rawlsian Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, 30 Sci. & Eng. Ethics 46 (2024):

- The popularisation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies has sparked discussion about their ethical implications. This development has forced governmental organisations, NGOs, and private companies to react and draft ethics guidelines for future development of ethical AI systems. Whereas many ethics guidelines address values familiar to ethicists, they seem to lack in ethical justifications. Furthermore, most tend to neglect the impact of AI on democracy, governance, and public deliberation. Existing research suggest, however, that AI can threaten key elements of western democracies that are ethically relevant. In this paper, Rawls’s theory of justice is applied to draft a set of guidelines for organisations and policy-makers to guide AI development towards a more ethical direction. The goal is to contribute to the broadening of the discussion on AI ethics by exploring the possibility of constructing AI ethics guidelines that are philosophically justified and take a broader perspective of societal justice. The paper discusses how Rawls’s theory of justice as fairness and its key concepts relate to the ongoing developments in AI ethics and gives a proposition of how principles that offer a foundation for operationalising AI ethics in practice could look like if aligned with Rawls’s theory of justice as fairness.

- European Parliamentary Research Service, European framework on ethical aspects of artificial intelligence, robotics and related technologies (Sept. 2020)

- European Parliamentary Research Service, The ethics of artificial intelligence: Issues and initiatives (March 2020).

- Meta, AI Alliance Launches as an International Community of Leading Technology Developers, Researchers, and Adopters Collaborating Together to Advance Open, Safe, Responsible AI December 4, 2023.

- Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, Ethics of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (Apr. 30, 2020).

- ISO, Building a responsible AI: How to manage the AI ethics debate (Jan. 2025) :

- Responsible AI is the practice of developing and using AI systems in a way that benefits society while minimizing the risk of negative consequences. It’s about creating AI technologies that not only advance our capabilities, but also address ethical concerns – particularly with regard to bias, transparency and privacy. This includes tackling issues such as the misuse of personal data, biased algorithms, and the potential for AI to perpetuate or exacerbate existing inequalities. The goal is to build trustworthy AI systems that are, all at once, reliable, fair and aligned with human values.

- Thilo Hagendorff, The Ethics of AI Ethics: An Evaluation of Guidelines, 30 Minds and Machines 99 (2020)

- Brent Mittelstadt, Principles Alone Cannot Guarantee Ethical AI, Nature Machine Intelligence (Nov. 5, 2019).

- Rodrigo Ochigame, The Invention of “Ethical AI”: How Big Tech Manipulates Academia to Avoid Regulation, The Intercept (Dec. 20, 2019).

Specific Perspectives

- (*) Chinmayi Sharma, AI’s Hippocratic Oath, __ Wash U. L. Rev __ (Forthcoming):

- Diagnosing diseases, creating artwork, offering companionship, analyzing data, and securing our infrastructure—artificial intelligence (AI) does it all. But it does not always do it well. AI can be wrong, biased, and manipulative. It has convinced people to commit suicide, starve themselves, arrest innocent people, discriminate based on race, radicalize in support of terrorist causes, and spread misinformation. All without betraying how it functions or what went wrong.A burgeoning body of scholarship enumerates AI harms and proposes solutions. This Article diverges from that scholarship to argue that the heart of the problem is not the technology but its creators: AI engineers who either don’t know how to, or are told not to, build better systems. Today, AI engineers act at the behest of self-interested companies pursuing profit, not safe, socially beneficial products. The government lacks the agility and expertise to address bad AI engineering practices on its best day. On its worst day, the government falls prey to industry’s siren song. Litigation doesn’t fare much better; plaintiffs have had little success challenging technology companies in court.This Article proposes another way: professionalizing AI engineering. Require AI engineers to obtain licenses to build commercial AI products, push them to collaborate on scientifically-supported, domain-specific technical standards, and charge them with policing themselves. This Article’s proposal addresses AI harms at their inception, influencing the very engineering decisions that give rise to them in the first place. By wresting control over information and system design away from companies and handing it to AI engineers, professionalization engenders trustworthy AI by design. Beyond recommending the specific policy solution of professionalization, this Article seeks to shift the discourse on AI away from an emphasis on light-touch, ex post solutions that address already-created products to a greater focus on ex ante controls that precede AI development. We’ve used this playbook before in fields requiring a high level of expertise where a duty to the public welfare must trump business motivations. What if, like doctors, AI engineers also vowed to do no harm?

- (*) Pasclae Fung & Hubert Etienne, Confucius, cyberpunk and Mr. Science: comparing AI ethics principles between China and the EU, 3 AI and Ethics 505 (2023):

- We propose a comparative analysis of the AI ethical guidelines endorsed by China (from the Chinese National New Gen-eration Artificial Intelligence Governance Professional Committee) and by the EU (from the European High-level Expert Group on AI). We show that behind an apparent likeness in the concepts mobilized, the two documents largely differ in their normative approaches, which we explain by distinct ambitions resulting from different philosophical traditions, cultural heritages and historical contexts. In highlighting such differences, we show that it is erroneous to believe that a similarity in concepts necessarily translates into a similarity in ethics as even the same words may have different meanings from a country to another—as exemplified by that of “privacy”. It would, therefore, be erroneous to believe that the world would have adopted a common set of ethical principles in only three years. China and the EU, however, share a common scientific method, inherited in the former from the “Chinese Enlightenment”, which could contribute to better collaboration and understanding in the building of technical standards for the implementation of such ethics principles.

- Ben Green, Data Science as Political Action: Grounding Data Science in a Politics of Justice (Jan 14, 2019).

- IEEE, Ethically Aligned Design: A Vision for Prioritizing Human Well-being with Autonomous and Intelligent Systems (1st Ed.) (valuable but long).

- Kinfe Yilma, African AI Ethics?—The Role of AI Ethics Initiatives in Africa (Aug 13, 2024):

- A recent concern in Artificial Intelligence (AI) ethics scholarship is the overly western-centric nature of ongoing AI ethics discourse and initiatives. This has recently prompted many commentators to warn the emergence of an epistemic injustice or ‘ethical colonialism’. This article examines the extent to which Ubuntu, and AI strategies in Africa articulate an African perspective of AI, and hence address the epistemic injustice in AI ethics. I argue that neither the normative structure of Ubuntu nor recent AI strategies offer a clear, coherent and practicable framework of ‘African AI ethics’. I further show that the much-touted ‘African’ ethics of Ubuntu is rarely referenced or implied in the other national or continental AI strategy initiatives.

- Dorine Eva van Norren, The ethics of artificial intelligence, UNESCO and the African Ubuntu perspective, 21 J. Info., Communication and Ethics in Society (Dec. 2022):

- This paper aims to demonstrate the relevance of worldviews of the global south to debates of artificial intelligence, enhancing the human rights debate on artificial intelligence (AI) and critically reviewing the paper of UNESCO Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology (COMEST) that preceded the drafting of the UNESCO guidelines on AI. Different value systems may lead to different choices in programming and application of AI. Programming languages may acerbate existing biases as a people’s worldview is captured in its language. What are the implications for AI when seen from a collective ontology? Ubuntu (I am a person through other persons) starts from collective morals rather than individual ethics. [….] “Metaphysically, Ubuntu and its conception of social personhood (attained during one’s life) largely rejects transhumanism. When confronted with economic choices, Ubuntu favors sharing above competition and thus an anticapitalist logic of equitable distribution of AI benefits, humaneness and nonexploitation. When confronted with issues of privacy, Ubuntu emphasizes transparency to group members, rather than individual privacy, yet it calls for stronger (group privacy) protection. In democratic terms, it promotes consensus decision-making over representative democracy. Certain applications of AI may be more controversial in Africa than in other parts of the world, like care for the elderly, that deserve the utmost respect and attention, and which builds moral personhood. At the same time, AI may be helpful, as care from the home and community is encouraged from an Ubuntu perspective. The report on AI and ethics of the UNESCO World COMEST formulated principles as input, which are analyzed from the African ontological point of view. COMEST departs from “universal” concepts of individual human rights, sustainability and good governance which are not necessarily fully compatible with relatedness, including future and past generations. Next to rules based approaches, which may hamper diversity, bottom-up approaches are needed with intercultural deep learning algorithms.”

- David Zvi Kalman, 3 reasons why A.I. must be a religious issue and not just a peripheral one, Jello Menorah (Dec. 8, 2022).

Ethical Problems/Hypotheticals

- (*) Gladstone AI, Defense in Depth: An Action Plan to Increase the Safety and Security of Advanced AI (Feb. 26, 2024):

- The recent explosion of progress in advanced artificial intelligence (AI) has brought great opportunities, but it is also creating entirely new categories of weapons of mass destruction-like (WMD-like) and WMD-enabling catastrophic risks. A key driver of 1 these risks is an acute competitive dynamic among the frontier AI labs that are 2 building the world’s most advanced AI systems. All of these labs have openly declared an intent or expectation to achieve human-level and superhuman artificial general intelligence (AGI) — a transformative technology with profound implications for 3 democratic governance and global security — by the end of this decade or earlier.

The risks associated with these developments are globa(*)l in scope, have deeply technical origins, and are evolving quickly. As a result, policymakers face a diminishing opportunity to introduce technically informed safeguards that can balance these considerations and ensure advanced AI is developed and adopted responsibly. These safeguards are essential to address the critical national security gaps that are rapidly emerging as this technology progresses.

Frontier lab executives and staff have publicly acknowledged these dangers. Nonetheless, competitive pressures continue to push them to accelerate their investments in AI capabilities at the expense of safety and security. The prospect of inadequate security at frontier AI labs raises the risk that the world’s most advanced AI systems could be stolen from their U.S. developers, and then that they could at some point lose control of the AI systems they themselves are developing , with potentially devastating consequences to global security.

- The recent explosion of progress in advanced artificial intelligence (AI) has brought great opportunities, but it is also creating entirely new categories of weapons of mass destruction-like (WMD-like) and WMD-enabling catastrophic risks. A key driver of 1 these risks is an acute competitive dynamic among the frontier AI labs that are 2 building the world’s most advanced AI systems. All of these labs have openly declared an intent or expectation to achieve human-level and superhuman artificial general intelligence (AGI) — a transformative technology with profound implications for 3 democratic governance and global security — by the end of this decade or earlier.

- (*) Christian Terwiesch and Lennart Meincke, The AI Ethicist: Fact or Fiction? (Working Paper, Oct, 11, 2023):